Anton Veenstra's Textile Blog

my textile career from 1975

Category Archives: hippies

social commentary

Tapestry and social protest.

It was at university, during a first year English literature lecture that the concept of “universality” was explained. An author attempted to reach the widest audience, to do so he assumed a persona that you could easily relate to. What resulted was the cliche “a dead, white, middle class male”. By upbringing, I was anything but that; my mother had arrived in a strange southern land a European refugee and I had been born behind a wire fence. I grew up a “reffo kid”, classmates chanted “go back to where you came from” in the playground. I realised I was “ethnic” while they were ordinary. Later as I grew into my adult identity, I confronted societal homophobia, plus the effects of childhood abuse by a catholic pedophile priest. I recount this not for brownie points, but as things to confront in my art.

As a gay man invisibility was the reverse of universality; nowhere could I find my own kind, people who had gone before, clear accounts of their feelings, their needs, their struggles. We were all underground. However by the mid 1970’s, women were demanding equal rights, indigenous peoples struggled for a place, and migrants and refugees sought an identity. The mainstream male enjoyed beer and cricket, and thought about little else.

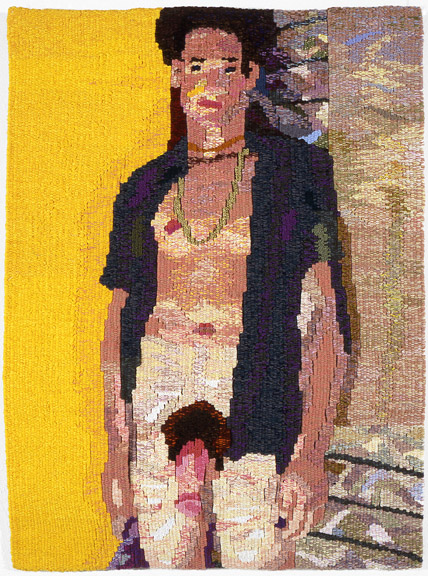

I settled on a textile medium, having written adolescent poetry for a decade, but found words a barrier to communication. The 1970’s was a decade when counterculture people were experimenting in all directions; the first tapestry I wove exuded a strong visceral impact; I was certain it could TELL A STORY. My earliest works were self portraits, and images of plants, birds and animals, in other words a mirror of my world with my reflection in a corner examining it all. Soon I began to create homoerotic images, not to shock outsiders, although that soon seemed inevitable, but to assert the qualities of the homintern, the gay brotherhood, gay liberation. As an example, when the Object Gallery produced the second Gay Mardi Gras show which included my work, Material Boys Unzipped in 1999, a critic remarked about the genital size of Odalisk, while a fellow craftsperson’s reaction to the work was that it contained exactly the right combination of joyous colour that a tapestry should have.

I began to realise that colour, texture and luminosity were the triangulation of my art practice; however, as all tapestry weavers will admit, there is one huge drawback to the medium. If the focus of your inspiration is a detail near the top of the cartoon, in other words, possibly six months of weaving away, the drudgery can grind away at the enthusiasm with which the work began. Often the will to complete it quickly dissipates and the work is abandoned. One solution I arrived at was experimenting with a different textile medium, that allowed the freedom painters had, to begin anywhere on the surface of the work. This was to create a mosaic which I called an “assemblage” of buttons sewn with upholsterer’s thread onto stretched canvas.

I had exhibited, in an expression of solidarity, during the annual Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras, now an international event; people sometimes bought my work from those venues, but even feedback became sparse. I decided that mostly women collected textile work, and they had no desire to collect homoerotica. I decided on a new direction, enrolled at COFA the College of Fine Arts in Paddington, Sydney in 2000 to undertake my Master of Design Honours degree. My thesis would be my parents’ postwar migration and my own experience growing up in a migrant household. My birth in a detention camp, I felt, equipped me to understand the experience of successive waves of refugees to Australia: the Vietnamese in the 1970’s, Iraqis and Afghanis in recent years. Looking at my mother’s Slovenian folk culture, her country having been once part of the Ottoman empire, led to other insights. Visually, the Slovenian national flower, the mini carnation with fretted petals was also to be found depicted on the tilework of Turkish mosques and on their textiles.

This was a convenient link to Edward Said’s concept of “orientalism” and its recent manifestation in the wars between the west and Islamic culture. I assumed no particular stance in this area at first; I had travelled widely in the middle east in 1979: Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Turkey, as well as countries from which Islam had retreated: Greece, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria. I greatly admired the second generation of folk tapestries from Wissa Wassef, the Iranian carpet menders outside the El Azhar mosque in Cairo with their exquisite silk yarns, an opium-addicted worker sitting in the Han Halili souk, sewing appliqued buntings that decorated the streets in preparation for the visit of the Israeli President Begin.

My protest came later, when I read of the honour killings and arrests of women and gay men by the “chastity police” of Iran, the foregone conclusion of sentencing by the Ayatollahs in the courts and the casual executions from cherry pickers in the market places of “religion cities” like Mashhad. I commemorated the execution of two youths on a carpet called the Hanging Garden. I have yet to come to terms with avid onlookers compulsively filming the event on their mobile phones. However, before we point the finger of indignation, it should be said that public execution was enjoyed as entertainment in the time of Queen Elizabeth 1. There, witches and sodomites were hanged or burned, the original meaning of the word “faggot” being a gay man wrapped in a bundle of sticks as fuel for the witch’s pyre. I personally feel that fundamentalism whether Abrahamic, catholic or other is a latter day version of the Inquisition, with suitably modern punishments like aversion therapy.

I remain determined to critique such babarities in my work; tapestry was once the triumphal celebration of the conqueror; now, it is capable of conveying the personal narrative of the marginalised. One of my recent tapestries is a portrait of a clown in a turn of last century English circus; I was determined to express the young man’s poise, his admirable dignity while dressed in colourful absurdity; I was intent on avoiding caricature. This continues my on-again off-again series of portraits, which includes two images of Gareth Thomas, a Welsh footballer who achieved national prominence, all the while struggling to come to terms with his homosexuality. They are simply head & shoulder shots which show the harmony of massive strength and inner peace. In this I have arrived at an understanding of a younger gay audience’s rejection of overt sexual imagery; perhaps the yet unresolved catastrophe of the Aids epidemic has played its part in this. I suspect it is a way a younger gay community is building links with wider communities on neutral grounds.

My impatience as a young weaver has disappeared with the maturity that time brings; the first step towards a solution had been to allow slits along adjacent vertical colour areas; these soon became unfortunate gaps once the work was cut from the loom. One day, while giving a talk at Newcastle University I saw the Swedish weaver Annika Eckdahl at work on a very large piece. Her technique was to use an interlocking join along adjacent vertical colour areas. Once a youthful impatience to weave quickly was overcome, it proved a satisfying method of creating shape, pattern and texture. In a Susan Maffei + Archie Brennan workshop in Sydney, the latter had admonished his class against weaving too quickly. After all, packing the weft around the row of warps involves the patient dance of the bobbin point, nothing else allows the yarn to sit flat on the surface. Textile artist Diana Wood Conroy has exhorted fellow weavers to make a virtue from what seems a chore; “Our work is a slow revolution”, she says.

Byline: Born to Dutch + Slovenian parents, I completed my Master of Design [Hons] degree at COFA in 2003. I contributed to socially critical art events: The Blake Prize for Religious Art [From Refugee to Citizen, the Compassionate Society] 2007; The New Social Commentary at Warnambool Gallery in 2006 [The Hanging Garden] and 2008 [Authorised to Instruct, a critique of catholic clerical pedophilia]. I weave tapestry and construct button assemblages or mosaics. For a more comprehensive examination of the above issues, please refer to my blog. http://antonveenstratextiles.com

Blond Boy with Bike.

Mary Schoeser said of her selection for Textile: Art of Mankind, that she spurned prevaling fashion.

After all, Oscar Wilde declared that fashion was an ugliness so extreme it had to be replaced every six months.

In the note Shoeser added to explain the photo of my work, she includes my description of the work, the fact that my parents were interned in Cowra Migrant Camp after World War Two, that I was born inside the camp. When I visited Cowra Tourist Information Centre as an adult for an exhibition that Cowra Gallery was holding, which would include four of my works, I met a person there who said she had been a nurse when I was born in the camp. She was adamant that I would have been born in the local hospital, as if that improved matters. A booklet outlining recollections of interned migrants mentions that in 1950, the year my mum was pregnant with me, the women of the camp went on strike to demand better food for those who were pregnant. This was reluctantly granted.

I have shown friends my page in Schoeser’s book; the reaction has sometimes been oblique and unexpected. A clear offshoot of modernism is the assertion of personal narratives that deviated from the modernist stereotype of universalism. Art generally had been produced by dead white, middle class males. I detected a tone in some people’s reactions that, in some way, I was pushing myself forward, a vulgar display of subjectivism.

By contrast, I would assert that culture has deviated from the broad highway of universalism, the expression of the priviledged establishment, to include the voices of colonised and marginalised people.

Tonight on ABC TV, Senator Penny Wong, a Chinese lesbian member of the federal government stepped forward to explain the government’s revision of anti-discrimination legislation. When one journalist made the mistake of asserting that the new bill would allow “professional” whingers to make false accusations, Senator Wong very quietly but menacingly said that there were so many things wrong with his analysis that she did not know where to begin. She said that, in her experience, people enduring discrimination generally were silent for too long. This is my experience with the narrative of my birth in Australia. My early years was such a hectic patchwork of negotiating languages, negotiating domestic culture and the public culture of the classroom and school yard. It took many years to place all these elements into perspective. Further down the track was enduring the attention of a pedophiliac priest when I was 12, coming to terms with being gay in my late teens while studying in high school and university. The so-called universalist backdrop for all of this was the Vietnam War, the hippie era of the late 1960’s, marijuana and lysergic acid, the various protest movements in Sydney, against apartheit, against corrupt development, for feminism and gay liberation.

Clearly, it was going to be in my 50’s before I was ready to re-assess my upbringing. I presented it in an art context already annotated by recent waves of immigration, Vietnamese and most recently Iraqi and Afghanistani refugees. In spite of the protest at Cronulla Beach and the rise of individuals like Pauline Hanson, I hesitate to use the word “racist” of ordinary Australians. Working class peoples post WW2 did not have the money to travel and inevitably broaden their minds; at every level of our society I believe it to be a universal pleasure to see newcomers settle into our country, develop the broad, friendly speech patterns and aspire to the better way of life that hard work and ambition make possible.

But the narrative should be remembered and recounted; it deserves to be embodied in our artforms and to become part of our national cultural identity.